Friday, January 27, 2012

Is Chivalry Dead? Would That Wishing Made it So

So here’s the thing. Somewhere along the way, people started thinking that “chivalry” and “courtesy” are the same thing. They’re not. Holding the door for the person behind you, regardless of your respective gender presentations is courtesy. Offering your seat on the bus to the person with their arms full is courteous, regardless of whether they’re wearing heels and a skirt. If you are a dude and you hold the door for women but not for men, you aren’t chivalrous, you’re just a douchebag. And if you get to the door first and the woman behind you has her hands full but you don’t hold the door because, hey feminism, well then you’re just an asshole.

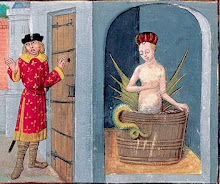

Because let’s be clear what we’re talking about when we talk about chivalry. As much as modern chivalry advocates would have us believe that chivalry and courtesy are the same, chivalry is a system in which women of a certain social class agree to sacrifice autonomy and their status as human beings so that men of the same social class will protect them as valuable property from other men who may want to damage said property. A system where men of noble rank were free to rape peasant women, because courtesy was wasted on such a woman who couldn’t feel love. A system where as long as a man was unfaithful only with his libido, not his heart, it was all good, but a woman who committed adultery could be killed for dishonoring herself and her family.

If you are woman of a lower social class, you are fair game.

If you are not appropriately meek and virtuous, you are fair game.

If you slip from your pedestal and demonstrate any human flaw, you fall down here with the rest of the bitches and whores. You are fair game.

I struggle with femininity. I love makeup and always have. I love sparkles and flowers and mermaids and rainbows, and always have. I enjoy “girl-drag” from time to time—the trappings of traditional femininity.

But to be feminine in our culture is to be incompetent. It is to throw like a girl. It is to cry like a little girl. It is to be delicate. Sexy, but not sexual. Smart, but not too smart. Quiet. Submissive. I am none of these things. I laugh too loud at raunchy jokes. I am smart and I don’t hide it. I like sex. I don’t stroke egos. I try to be kind, but I do not submit. I’ve been on the pedestal, and the price was too high. There’s no wiggle room, no room for the inevitable failure. I am not a goddess. I am not La Belle Dame Sans Merci. I am not the pure, virtuous ideal. I am a human woman with human flaws and human passions.

So when I read that—just the ones worth dying for—600 years of chivalry’s baggage hit me like a sleeper wave. 600 years’ worth of messages telling me to be desirable but unattainable, of my honor being reduced to what’s between my legs, of my worth being determined by how closely I can live up to the ideal—how well I balance on the pedestal. I was reminded that as a flawed person, I am nothing but a bitch and a whore, certainly not a goddess worth dying for.

This is chivalry’s legacy. It is a world where an 11 year old girl is blamed for her own gang-rape because she is seen as low-class. It is men who scream epithets at women who have the gall to refuse them, however politely, because their honor has been insulted. It is women who slut-shame, thinking that their virtue will keep them safe. Chivalry can’t die fast enough, as far as I’m concerned. If that makes me not worth dying for, so be it. The women in chivalric romances who are worth dying for all come to depressing ends—both the cause and the victims of death and tragedy. I have no interest in the simple joys of maidenhood. Worth dying for? Screw that. I’d rather be worth living for.

Friday, September 18, 2009

A Fairytale

Edited to add context: This story is the result of an exercise I set myself: to draft a tellable adaptation of a traditional "fairy wife" tale that would be appropriate for my Renaissance Faire character (a prosperous carpenter's wife" to tell. I chose to adapt "The Sky Woman's Basket" because its themes moved me very deeply. That said, I recognize the problematic history of American and European individuals and entities co-opting the culture of a colonized people for their own entertainment. This is not a story I would tell, I think. In performance I would not move the action to England, but remain truer to the original tale. The version I heard can be enjoyed here.

Once in this village there lived a man with a flock of sheep. The yarn spun from their wool was as light and fine as Venetian silk and every day he took them to pasture in the fields with the greenest and sweetest grass. Each year when the time came to shear them, his sheep gave him the finest wool in Derbyshire.

One year, the night before shearing day, the man gathered his sheep and locked them in their pen. He slept that night, dreaming of the fine wool he would gather the next day. When he awoke, he gathered his tools and his helpers and went out to the pen. There he found half the sheep already shorn! “There is a thief in the village,” thought the man. “Tonight I will keep watch and catch whoever it is when they come to finish the job!”

So that night the man locked his sheep in their pen and pretended to go to sleep. While he watched, nine beautiful maidens walked out of the nearby forest, each carrying shears and a basket. The maidens called to the sheep, who came willingingly and lay down for them while the maidens harvested their wool. Then the maidens turned to go back to the forest. The man ran after them crying “Stop! Thieves!” but they faded back into the trees.

He managed to catch up with the last maiden, who had dropped her basket and had to stop. He grabbed her arm as she started to retreat into the forest. “Woman!” he bellowed, “Thou art a thief and must repay me for what thou hast stolen. Stay and work for me for nine months and thy debt shall be paid.” The maiden thought a moment and said “That is fair. I will stay and work for you for nine months.”

Now the day came when the nine months had passed. The man went to the maiden as she kneaded the day’s bread and said, “Thy debt hath been paid, thou mayest leave me this day. But I have grown fond of thee these nine months, and I pray thee, stay and be mine own wife.”

And the maiden thought a moment and said “Thou art a good man, and I too have grown fond of thee. I will stay and be thy wife an thou makest me one promise. Promise me thou shalt ne’er look inside my basket.”

The man looked at the closed basket in the corner where it had sat ignored these many months. He laughed. “I promise thee, silly woman! What care I for baskets?”

So the man and the maiden were married and lived very happily for nine years. She bore him nine children, all tall and beauteous and wise, and their fields and flocks were most prosperous. From time to time, the man would look at the basket whither it sat in the corner and wonder what it contained, but then he would look at his beautiful and clever wife and think “What care I for baskets?”

One day his wife had gone to the market in the village and as he worked throughout the day, his thoughts returned to the basket again and again. What secrets did it hold? What did his wife hide from him? Distrust grew in him like a canker until he could stand it no more. He went inside, threw the lid from the basket, looked inside and saw—nothing.

He laughed at his foolishness, and that of his wife and turned to retrieve the basket’s lid. As he did, he saw his wife standing in the door. “What hast thou done, husband!” she cried. “Silly woman,” the man laughed, “there is nothing in this basket!”

His wife looked him, picked up the lid, and replaced it on the basket. Then she picked it up and walked out the door and back into the forest, never to be seen again. And when the man called to their nine handsome children to come home that night, they too had disappeared.

The man spent the rest of his days searching the forest for his wife and children. His sheep grew thin and dirty, his fields turned to weeds. The men of the village have always said that she left because he dishonored her. A promise is a promise, after all, e’en one made to a woman. And their wives nod their heads in agreement.

But at the well and oven and market stalls, the women tell each other their truth. They say the maiden from the forest left because the man saw nothing but an empty basket.

This story is my adaptation of a traditional story (possibly Zulu) called "The Sky Woman's Basket" as told by master storyteller David Novak. It is inspired by the work of storyteller Janice Del Negro of Dominican University in Illinois, as well as by "The Seal Maiden", "The Crane Wife", "The Tale of Melusine", and other ancient stories of betrayed fairy wives. It also owes a little debt of gratitude to the story "A Jury of Her Peers" by Susan Glaspell.

Friday, January 23, 2009

Things that make me happy

Please do your best to ignore Chris Matthews, who is annoying, and Michelle Bernard who usually is annoying, but not as much here, although I'm not sure what the heck she's talking about when she mentions a shift in left-of-center feminism.

Wednesday, November 12, 2008

I'm not inspired. No, really.

Yes, I know it was last week. Hush.

Don't get me wrong. The fact that this country elected an African-American person President? Inspiring. The sight of Jesse Jackson with tears streaming down his face? Awesome. Truly. The footage of people from all walks of life dancing and crying and screaming for joy? Beautiful.

His speech? Eh.

It's taken me this long to break down and analyze my reaction. I mean, for the last eight years the only presidential speeches I've listened to have been written by Aaron Sorkin. There was always the possibility that the problem was just that Barack Obama wasn't Josiah Bartlet.

I've come to the conclusion that that's not the problem. The problem is women and action.

Obama mentions women in three places in his speech--twice specific women and once as a group. The first time, women are in support positions--his wife and daughters, sisters, and grandmother. They are remarkable only for their relationship to him, their support. Classic "behind every good man" stuff.

The second time he mentions a woman, he talks about 106 year-old Ann Nixon Cooper. The whole discussion of Mrs. Cooper centers around what she's seen. There is no mention of what she has done. She is a witness--passive, removed. And when he goes on to speculate about what his own daughters will see if they live into the next century, he asks "what progress will we have made?" But his daughters are described, like Mrs. Cooper, as passive witnesses.

Only once does Obama describe women in an active role--when he describes the suffragists. But they are separate from women today; they are removed from today's struggles as described in Obama's speech. Women are never specifically included in his call to action. He mentions Republicans, Democrats, gays, disabled folks, African Americans, Latinos, Asians, and Native Americans. He does not include women.

I will be the first to admit that everything I know about Presidential speechwriting I learned from Toby Ziegler and Sam Seaborn on The West Wing. But I don't think that there are many accidents in a speech like this. Were women excluded deliberately? Were they originally included but then cut from the final draft? Maybe Obama and his speechwriters just didn't notice that they assigned women the same passive support roles we've been assigned since before the founding of this country.

Whatever the explanation, they missed an opportunity to inspire this woman to action. I will act, because it is not in my nature to be passive. But inspiration? Not so much.